A constant high-pitched hum of a train engine surrounded me as I descended to the platform on an escalator. The train only had three cars and there weren’t many passengers in line. I stood behind some other backpackers, who were always easy to spot by the over-the-top baggage. The brisk night air carried the sound of the engine so clearly into the empty spaces around us, muffling any conversation that occasionally and briefly arose among the weary passengers. The line moved slowly toward the train doors, and an old man in a crew uniform checked my ticket. “Dimitrovgrad?” he asked curtly. “Yes,” I replied, “we are going there, right?” The man simply nodded and let me onto the train. The narrow corridor of the train car was brightly lit, but most of the cabins were empty and dark. My cabin was in the middle, and two other passengers were already there, busy settling down.

The three of us in the cabin started talking about where we were going and what we thought of Istanbul. Sitting next to me by the window was Giuseppe, a talkative, middle-aged Italian dude. He had a talent for passionately discussing the most random topics for hours. Sometimes I couldn’t follow everything that he said due to the thick accent, but his stories and points of view were quite interesting. The other passenger sitting across from me was a Swiss backpacker, Rafael, who said that he was visiting Istanbul for a couple of days because he had always wanted to see it. He said that he didn’t end up going to any of the popular places like Hagia Sophia because the ticket prices were too steep. Glad to find I wasn’t the only one who had skipped those well-known destinations, I admitted that I had done the same thing. Only Giuseppe, who was a bit more mature and experienced than we were, said that they were probably worth seeing once in a lifetime but still agreed that he couldn’t justify the current price. While we were talking, the train had already departed, and the old conductor opened the sliding door and handed out bedsheets and pillows. “We will arrive at the passport control at around 3:00AM,” he announced tersely and slid the door shut.

My eyelids were heavy as I had barely slept since leaving Tbilisi on a bus two days ago. But the conversation in the cabin was just warming up and no one showed any intention of converting the seats into beds. At first, we talked about our lives in our respective countries and the topic somehow moved on to the modern society and the economic systems. Giuseppe was something of an anarchist and argued that the people had become slaves to the government and corporations. He added that someday everyone would be liberated from the system, but that would happen very slowly because it was impossible to change other people’s minds, and we should never try. “There was an Italian guy,” Giuseppe said, “very smart, very good ideas. He went overseas to change people’s minds. But, no, he failed.” I didn’t follow the story entirely but he went on about his story and concluded that, “No, we should never try. We should never try.” Then Giuseppe began telling us about the festivals that he had been to over the years and said that those were blueprints for an alternative society–one without government, mass media, or corporations to rule over people. “Listen to this,” he said as he put on a song about the unity of mankind in different languages. “It’s possible, it’s possible.” I didn’t really buy the whole thing and the song was a bit cheesy, but I didn’t mind. The train sped through the night as the tune played on.

The conversation then turned to where we were all headed. Both Rafael and Giuseppe were heading to Sofia. Giuseppe, who was well-traveled and had already been to Sofia a number of times, gladly shared all his tips about where to stay and visit. These worked up my curiosity, and I wished that I had the luxury of time to tag along. “Where are you headed?” Rafael asked me. I said that I was going to hop off at Dimitrovgrad to hopefully reach Dublin in a few days. Rafael and Giuseppe became quite confused upon learning my plan and asked dubiously, “Dublin? How?” I explained that I was trying to get to Bucharest and then hopefully to Budapest, and that I was planning to figure out the rest on the way. “You will go to Ruse?” Rafael asked with a heavy French accent. “Yes,” I answered with an uncertain voice, “I will go to Dimitrovgrad, Gorna, Ruse, and cross into Romania.” Trying to help, Rafael and Giuseppe looked up the train information and told me that my route wasn’t possible. Rafael found that the train might not be running between Gorna and Ruse. And he said that, even though I somehow could make it to Ruse, the border crossing would take too long for me to safely make the connection in Bucharest. “Maybe come with us to Sofia,” Giuseppe invited me. “Yeah, maybe you can figure something out in Sofia,” Rafael added, trying to dissuade me from the foolish pursuit that seemed to lead only to certain failure. But I couldn’t compromise–the road ahead, with all its uncertainty, was the one I needed to be on.

It was almost midnight but no one wanted to go to sleep except me. I was crashing pretty hard due partly from hunger and partly from fatigue, as I hadn’t eaten anything since lunch. I opened the box of brownies that I had picked up at Halkali and shared it with Rafael and Giuseppe. The conversation went on for a while until Rafael noticed my yawn and said, “Should we go to sleep?” “Maybe there is no point,” Giuseppe replied, “I think we will be at the border soon.” He looked ready to stay awake at least until we crossed into Bulgaria. Still, we soon folded the armrests and put down the bunk beds to set up our beds. I immediately fell asleep once the light was off.

Not long after, the old train conductor woke up the passengers with a loud announcement, calling out “Border!” while turning on the lights in our cabin. We all sprang up from our sleep and slowly got out of bed to head to the passport control. The time was already approaching 3:00AM. Since my connection train to Gorna was due to depart at 6:00AM from Dimitrovgrad, I asked the old man how long it would take to get to Dimitrovgrad. He said that it would take around fifty minutes. But when I asked how long the immigration would take, he couldn’t help much other than saying, “Who knows.” We all walked over to the old building near the platform and joined a small line for the passport control. The passport control was in an empty room with a window behind which the immigration officer sat. The area was cold and empty, and the small group of passengers, mostly still half asleep, stood around with hands in their pockets as the line moved slowly. There was a gray cat sitting right next to the immigration window with a suspicious expression on its face, scrutinizing everyone as they walked forward and presented their passports. Under its watchful eye, my request to exit Turkey was promptly granted. Rafael, Giuseppe, and I rushed back to our train car in the cold of the night.

At 3:30AM, the train crossed into Bulgaria but Giuseppe told us not to go to sleep yet because Bulgarian passport control was coming up. After a moment, the train pulled into Svelingrad and Bulgarian officers went around the car to collect everyone’s passports. The train stood still for about half an hour until everyone got their passports back and departed Svelingrad at 4:30AM. I was supposed to be at Dimitrovgrad already, but the train was running an hour late. I tried to get some sleep, hoping that the train would make up the time somehow.

After what felt like a short while, the old man opened the cabin door and woke me up from a light sleep. “Dimitrovgrad. Quick,” he said, standing next to the bunk bed. The train was already stationary on the platform. As I looked around and tried to gather myself, the old man said again, “Quick.” Sensing the urgency in his voice, I hastily grabbed my stuff and rushed off the train. Rafael and Giuseppe were still sleeping and I didn’t get to say goodbye. The platform at Dimitrovgrad was pretty much empty and had a large clock pointing at 5:30AM. The train was now coupled with much older-looking cars covered in graffiti. I darted into the station building to escape the freezing night air. It wasn’t much warmer there, but at least the ticket office was dimly lit and open. “Is the train to Gorna coming?” I asked a lady at the ticket office. “Yes,” she smiled and explained to me that the train was coming and that I didn’t need to reserve any seats.

By this time, I had enough time to wake up and come to my senses. I realized that, in my haste, I had left all my snacks and water on the Sofia train. Feeling rather thirsty and hungry, I tried to find a place to get some snacks. But the only thing I could find was a vending machine selling some chocolate bars. It only accepted some local currency whose symbol I didn’t recognize. So I walked out of the station and started roaming the nearby streets in hopes of finding some ATM or a supermarket. I was at least a little curious about the city anyway, and wanted to see some of it in the little time I had. Dimitrovgrad at 5:30AM before the dawn was rather bleak, although it gave an impression that it might redeem itself once the morning arrived. Nothing was open and I was the only one walking on the empty streets. A few taxi drivers who happened to be awake gave disinterested stares from behind their windshields. Although I didn’t mind the dreary atmosphere, I wasn’t dressed for the cold and there wasn’t much time to explore. I hurried back to the station to wait for the train to arrive, hoping that I could hold out until reaching Gorna despite having no food or water.

When I walked back to the station, the train I rode from Istanbul had already gone and the next train to Gorna was idling on the track. The old train had only two cars full of graffiti. The cars were divided into cabins that each consisted of three seats facing each other, and those seats were pretty worn out. The entire train was empty and dark, and there wasn’t even any crew member around. I just picked an empty cabin and sat by the window. The inside of the train was just as cold as the platform. Regretting that maybe I should have splurged on a proper jacket in the fancy mall back in Tashkent, I closed the windows and curled up with my hands deep in the pockets, my whole body shivering.

Just before the train departed, a large dude with a beard walked into the cabin and sat one seat apart from me near the aisle. I couldn’t help but put up my guard because he looked rather scary and the train was still dark with no one around. A few minutes later, the dude pointed to my charger and asked something in Bulgarian. It sounded like he was asking to borrow it. But all the power outlets weren’t working, and I told him “Ne rabotaet” (“It’s not working”) in case he understood Russian. He asked me “Russki?” (“Russian?”) and I replied, “Nyet, iz Avstralii” (“No, from Australia”). The dude didn’t speak much Russian or English, but he wanted to know what on earth I was doing in Bulgaria. When I told him that I was just traveling, he wore the biggest smile and remarked in a heavy accent, “Hi, welcome to Bulgaria!” All the tension that I had imagined suddenly dissolved. It reminded me that there are people outside my bubble, and they were just people.

My cabinmate soon fell asleep, head down, and the only thing that filled the train besides the silence was its rhythmic rattle along the track. Soon, the echoing beat of the train was mixed with a hint of daylight as the darkness that once looked invincible gave way to the break of dawn. The train was running along the idyllic Bulgarian countryside with vast fields dotted with occasional houses. When the street lights began to turn off one by one, crimson light flooded the horizon on the right side of the train and the sun slowly emerged from below. There was nothing but open fields outside the window. The blue sky was gradually revealing itself above and was just as boundless as the fields. The flawless sky was marked only by vapor trails from the night jets that must have passed through it before the sunrise. A conductor soon came around to check the tickets. After the dramatic sunrise, the surroundings became somewhat ordinary. There were actions in place of inactions, and warmth in place of cold. Everything looked so different in daylight and stirred my anticipation for the road ahead.

The train went through some towns and small villages separated by mountains and open land. My cabinmate was headed to a neighboring village not too far from Dimitrovgrad and got off at a small station along the way. He smiled and said, “Good luck,” before taking off. I looked out the window of the empty cabin for a while. There were still many unknowns ahead, but my mind didn’t even go there anymore. I realized that there was nothing much I could do anyway. If the trains ran late, I would miss the connections just as Rafael predicted, and in the unlikely event that the trains ran on time, things would flow as I had hoped. But I couldn’t magically make the trains run on time. Besides, I was feeling too lightheaded to worry about anything. I hadn’t had any proper meals since Istanbul and all I had for dinner last night was a couple of small brownies. I regretted having left all the snacks and water on the Sofia train. Then it suddenly occurred to me that there might be a bag of cookies left over from the bus ride from Tbilisi. I vaguely remembered offering some to Ludmilla on the morning of arriving in Istanbul, but I couldn’t say for sure whether I had finished the bag afterwards. Spurred by the hunger, I eagerly searched my backpack for the bag of cookies. But it was nowhere to be found. Desperation must have gotten the better of me, letting my imagination run wild.

The view from the window changed. The train had left the open, flat lands behind and was now venturing through heavy mountains. Thickets of trees and foliage passed the train window so closely that they were within the reach of my hands. The endless greenery was only interrupted by short tunnels that swallowed the train every once in a while, and occasional empty road crossings in the middle of nowhere. Sometimes the train would sound a short horn toward the nothingness ahead. Mostly, it moved slowly and silently through the mountains at a leisurely pace. The slowness didn’t bother me much at first because I had enough time to make the connecting train. It was almost 9:00AM and the train from Gorna toward Ruse was not going to depart until 11:30AM. One wrinkle was that the train might not be running as Rafael had warned. I was still hungry, and this time I really turned the entire backpack upside down to find some food. The bag of cookies turned out to be there at the bottom of the backpack, all crumpled up. I had never been more glad to see a snack and finished whatever was left in the bag. I got a bit thirsty but I felt I could wait another hour until arriving in Gorna, where I hoped to find some shops and ATMs.

From a small town in the middle of a mountain, a middle-aged lady hopped into my cabin and sat near the aisle where my previous cabinmate was sitting. “Privet” (“Hi”), I greeted on the off chance that she spoke Russian, and she replied back, “Privet, otkuda?” (“Hi, where are you from?”) When I told her that I was from Australia, she became kind of curious about how I ended up all the way here in the Bulgarian countryside. I just said that I was taking some time from work to travel and see what was out there. Then the conversation led to how I had been pretty much sleeping on buses and trains for the past couple of days to get here from the Caucasus. My Russian wasn’t strong enough to explain the reason for putting myself through all that, but the lady seemed to understand that I was just exploring. She would point out the monasteries and natural phenomena that passed by the train window and explain what those were. They appeared so far away and hidden in the dense forest and ridges. Their peaceful and mysterious atmosphere under the morning sun was intriguing, but with only six days left to go, they were as out of reach as they appeared from the window.

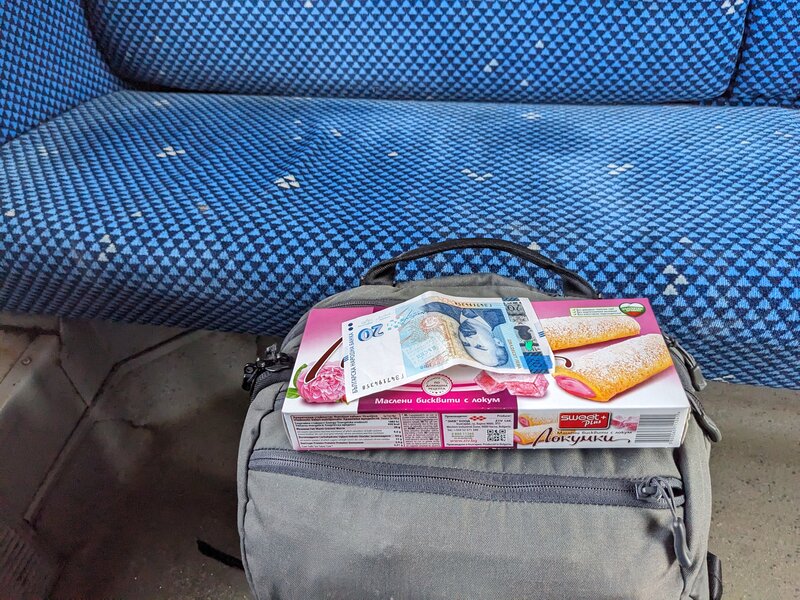

As the train slowed down and approached a small station in the middle of the forest, the lady gathered her things and prepared to leave. She said that she wasn’t going all the way to Gorna, and that Gorna station should be coming up shortly. Before heading out of the cabin, the lady took out a box of cookies from her handbag and handed it to me. “Vot, voz’mite” (“Here, take it”). Along with it, she also handed me a 20 lev note in the local currency. This outright kindness from a stranger confused me and I didn’t really know how to respond to it. I started fumbling my words and lying, for some reason, “Spasibo no ne nado, u menya yest’ yevro” (“Thanks, but there is no need, I already have euros”) even though I didn’t have any euros. The lady chuckled and responded, “Yevro ne rabotayet zdes’” (“Euros won’t work here”). She wished me luck and disappeared into the small, nameless station that had no signs. The train didn’t stop there for long. A uniformed station crew raised a flag to wave the train through, and the train eagerly covered the last remaining distance.

The train arrived at Gorna at around 11:00AM, about half an hour late but still before the connecting train toward Ruse, which was supposed to depart in half an hour. But I couldn’t find the connecting train anywhere. The departure board showed the train but there was no platform next to it. It just had some Bulgarian texts written in red, which didn’t bode well. In the main hall, I recognized some French backpackers that had boarded the same train at Istanbul last night. If they had traveled all the way here instead of going to Sofia, it was possible that they were also waiting for the same train. When I walked over in hopes that they might have some more information about the next train, a uniformed station crew member beat me to it and asked in English, “Are you going to Ruse?” She then said that trains weren’t running to Ruse, and that we needed to take a bus to a neighboring station. “Come with us,” she said calmly.

Before following her to the bus, I stopped by the station canteen to buy some much needed food and water. The canteen was a quaint room in the corner of the station where the time seemed frozen in the past. A grandma was tending an ancient wooden counter while reading a newspaper, and some guests were sitting by the tables on the side. On the counter were some thin loaves of bread wrapped crudely in thin plastic bags. They were perfect because there wasn’t enough time to sit down and have something to eat. I grabbed three bags of bread and a bottle of water and paid with the 20 lev note. The grandma put down the newspaper, took out a large ledger from under the desk, and wrote down the items and their price. When she gave me the change, I realized that I had barely spent any money and felt somewhat indebted for having accepted such a sum.

While I was there, two children who were sitting at a table on the side kept giggling and exclaiming, “Kitaets” (“A Chinese person”)! They eventually came up to me and greeted in English, “Hi,” awkwardly waving their hands. When I smiled and returned the greeting, they got really shy and ran off back to the table. Maybe they didn’t get many visitors with Asian appearances around here. This time I decided to let slide the unwritten code about clarifying the nationality when being mistaken for a Chinese person. For some reason it didn’t seem all that important.

Outside the station, a group of passengers were slowly gathering around two parked buses. “Is this going to Ruse?” I asked a fellow passenger who was waiting next to me with a folded bike. “Yes, I hope so. Looks like it is, isn’t it?” she replied. Coincidentally we were both headed to Bucharest. When I asked her about the folded bike, she said that she had been traveling around the world for the past six months on that thing, starting from the US West Coast, Japan, then all the way here. She was headed home to Amsterdam. I told her that I was headed in a similar direction to Dublin with hopes of then flying to Seattle. She politely said that she had been to Seattle a number of times and it was a wonderful place. The conversation was interrupted when the passengers all started boarding the bus. The two children from the canteen came out and waved at me, yelling “Goodbye!” I waved back and returned the “Goodbye!” They got shy again and ran back into the station.