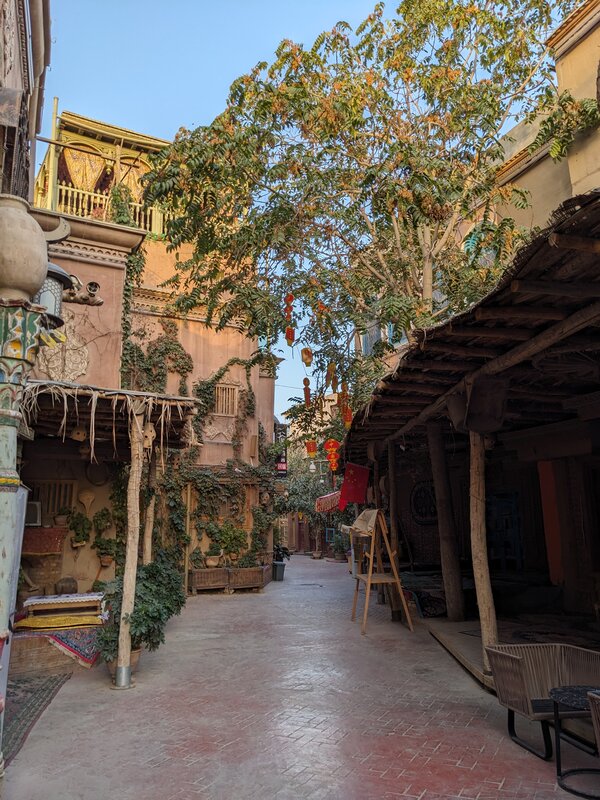

Evan and I were supposed to leave at around 10:00AM to pick up some other people that were also going to the westernmost stone monument of China. I woke up an hour before and headed out to buy some supplies–not only for the border crossing, but also for Evan’s road trip. Getting a few things for him felt like the least I could do. The old city was still slumbering in the cold morning air. Most things ran on unofficial Xinjiang time, and places weren’t going to open until later when the sun would have risen in this far western corner of China. So all I managed to buy were four pieces of small Uyghur bread and a few bottles of water. I managed to drop one of the pieces on the floor, reducing my meager food supply to three loaves of Uyghur bread, plus two large ones James had gifted me the night before. I also went to a bank to get some Chinese yuan in case I got stranded somewhere. I considered getting some US dollars, but according to the Chinese travelers at the hostel, it wasn’t possible to just walk into a bank and get US dollars.

The old city was running on the unofficial Xinjiang time, and therefore was still sleeping.

We left the hostel to pick up people staying at different parts of Kashgar. The city was bigger than I had realized, and it took some time to go around and gather everyone. By the time everyone was in the car and we were ready to leave, the city was wide awake and bustling. There were five of us in the car, all hailing from different parts of China and excited about going to the westernmost stone monument. One girl from Guangdong, Lucy, was particularly eager to see the sunset at the monument because it was supposed to be spectacular. Everyone in the car hit it off immediately, and it felt like they had known each other for years. I recalled similar vibes in our group that went to the Uyghur wedding the night before. I wondered whether I had been just lucky to keep meeting friendly people, or whether there were some cultural quirks I wasn’t aware of. At first, the new passengers didn’t know what to make of the presence of a foreign tourist who greeted them with broken Mandarin but became quite interested when Evan explained that I was a Korean heading to “Jierjisisitan.”

As the car drove through the busy morning streets, I was excited about heading to the border but everyone else in the car was getting kind of worried. My naive optimism didn’t transfer well, and people were stunned by my complete lack of preparation and knowledge about how to actually cross the border. Everyone started making phone calls and searching the Internet to try to figure out what I was going to need, while I sat quietly and awkwardly in the front seat. They said I might need a permit to exit China and took me to a government office on the outskirts of the city. But we couldn’t just waltz in and get a permit because the line there was pretty long. So the group helped me at least fill out a request form for the permit, which was all in Mandarin. A few curious locals that were waiting in line noticed this unusual scene and joined in to help. “Hold on to it at all times,” Lucy said as we walked out of the government building, “in case someone asks.” I carefully folded up the form and slid it into my pocket.

After this little detour, we finally set off to leave Kashgar. I could tell that we were leaving the city by the unfamiliar landscapes unfolding ahead. All of a sudden, there were strangely shaped rocks and bare mountains on the horizon. Those rocks had no vegetation, and the mountains stood naked in shades of clay. They bore strange patterns that must have been etched over countless years of wind and erosion. They must have stood there through it all, as travelers passed through, borders shifted, and empires and dynasties arose and fell. They had watched everything for eons, and now they were looking at me–all motionless, indifferent, and eternal. We drove toward those mountains, excited and letting out a chorus of exclamation at the spectacle. Soon we were surrounded by the mountains under the spotless autumn sky.

The strangely shaped mountains looked at us indifferently as we approached them.

At one point, we reached a major checkpoint where officers were inspecting every car and its passengers. All the cars seemed to be swiftly going through the line without any problems. When it was our turn, we rolled down the windows and presented our identifications. Seeing my foreign passport, the officer exchanged a few words with the others in the car and made us pull into a parking lot. I thought it was a bathroom break, but Evan explained to me that I needed to go to the nearby checkpoint building. “I will go with you,” he said. Inside of the building was pretty empty. An Uyghur man was speaking with an official behind a glass window and eventually walked out. I went up to the window and presented my passport. Evan and the official talked for a while, and eventually someone stepped out from the behind the glass, took my photo, and handed back my passport. We were cleared. The car continued on the lonely highway as the traffic became few and far between.

Two hours had passed since leaving Kashgar when we got off the highway and pulled into the town of Ulugqat. Kou An was supposed to be located there, and I could already see the signs pointing to it. The town was practically empty except for the occasional heavy-duty trucks that passed us with a deep rumble. As we approached Kou An, a wave of excitement and fear washed over me. Getting here was a good start, but I was a bit scared because I was still more than a hundred kilometers away from the border, with no clear plan for getting there. Doubts flooded my mind. Would I even clear the customs? How would I get to the border? What if either the Chinese or Kyrgyz side was closed by the time I got there? The clock was already pointing to one o’clock, and I began to wonder whether I should have started the day earlier. All these thoughts came crashing down as we pulled into the empty parking lot of Kou An.

Once I got out of the car and looked up at the imposing Chinese customs building, the nervousness gave way to naive excitement and optimism. The imaginary roads were no longer confined to my daydreams but were finally unfolding in front of my eyes. Everyone else was also excited to be in that unusual place too. “I wish I could keep driving to Kyrgyzstan too,” Lucy exclaimed. After celebrating our arrival with the new friends, I went to grab my backpack from the trunk but they told me to hold on. They were still unsure how I could reach the actual border.

We walked into the hall next to the main customs building, hoping to find transportation, but no one was there. The hall had some information about bus companies, so the friends started dialing the numbers one after another. But the only answer they got was that there was no transportation that day. There were some truck drivers hanging around, and Lucy asked them too and even tried to convince them to take me. But the drivers said that they weren’t able to take a passenger. The celebratory mood took a serious turn, and everyone spent a long time on the phone trying different options. I just awkwardly stood around, not knowing what was going on. Eventually, the friends told me that I couldn’t cross the border today, because there would be no way to reach it safely. They instead invited me to go with them to the stone monument and see the sunset. They said it was best to wait for a few days because there would be a bus from Kashgar station to Irkeshtam.

Everyone naively and prematurely celebrating the arrival at Kou An

Going to the stone monument sounded exciting, but I didn’t exactly have a few days to spare–it was already day seven of my twenty-four day race toward Dublin. The friends carefully and logically tried to explain to me that there was no transport, and that I wasn’t allowed to hitchhike or walk along the way because I needed to be on an authorized vehicle at the border. But I wouldn’t listen to logic and, like a stubborn child throwing a tantrum, insisted that I would hitchhike and find a way. Having come all this way, I couldn’t stop trying just because there was no bus running. I kept telling the friends that it would be fine to leave me at Kou An and that I would figure something out. Despite my persistence, abandoning me there was simply out of the question for them and they wouldn’t let me go.

This endless debate and search for options went on until two o’clock, when we realized that we were getting hungry. So we decided to have lunch in Ulugqat while trying to come up with some plan. While driving to the restaurant, the friends didn’t give up trying to persuade me to come over to the stone monument with them. I felt apologetic toward the group, because what was supposed to be a simple drop-off was turning into a major mission to get an ill-prepared foreigner safely across the border. During lunch, Lucy and Evan were constantly on their phones, practically calling every bus and tour operator in town. “Eat,” Lucy said in between the phone calls, “there won’t be any restaurants on the way.” She might have sensed that I wasn’t going to listen to reason and would go to the border no matter what. By the end of lunch, we still didn’t know how to get to the border, but we still headed back to Kou An. I wanted to pay for lunch, as I felt it was the least I could do, but the friends said it was out of the question.

Having a lunch with Lucy and Evan who were stuck babysitting this foolish tourist with an absurd plan

3:00PM. As the afternoon wore on, I was growing less confident about the possibility of crossing the border that day. Even if I could somehow reach the border, I wasn’t sure whether there would be enough time to go through it on both sides. If the border crossing closed down for the night, I might be stuck in the middle of nowhere. Everyone in the car was probably thinking along similar lines. But strangely, my obsession with crossing the border at any cost transcended any communication barriers or lack of context. Although I had never fully explained my reasons or circumstances for crossing the Irkeshtam Pass, the friends seemed to get it. They kept making calls as we drove back.

When we were almost at the entrance of Kou An, Evan suddenly got off the phone and made an announcement that seemed to bring some excitement. The friends explained that they might have found a bus that was willing to take me to the border. We excitedly took a U-turn to get back on the highway and drove toward where the map showed the bus company was located. But something didn’t bode well along the way, as there was nothing but empty fields around us. I was dubious about whether we could find a bus company way out there. It felt as though we would be lucky to find a single inhabitant in that area, let alone a bus company. As expected, only an empty field greeted us when we arrived at the destination. Evan made some more calls but no one picked up. We drove back to Kou An mostly in silence.

We arrived at Kou An for the third time that day. The arrival didn’t stir up much excitement or worry as it had previously. The only thing I felt was a vague sense of determination. 4:00PM. It was becoming less and less likely that I would even reach the border. But I wanted to at least try and fail. The car pulled over to the same spot where we had prematurely celebrated our first arrival to Kou An hours ago. The trunk popped open. As I grabbed my backpack and turned toward the customs building, Evan waved me over to an adjacent building. We climbed the empty stairs and ended up in an office filled with bright afternoon sunlight. Evan began having a conversation with a lady who was working there. I dropped my backpack on the floor along with the bag of Uyghur bread and bottles of water and started fidgeting around. There was some laughter in their conversation, as if a misunderstanding had been cleared up, which I took as a good sign.

At the end of the conversation, Evan turned to me and said that there would be a van in an hour that would take me to the border. He spoke into an app and showed me a translation. There was another passenger, and I just needed to wait for him to show up. At the border, another van would be waiting to get me across to the other side. He then added that everything was already paid for. After making the group waste many hours on the road and phone calls, I really couldn’t let him pay for the transport as well. But try as I might to convince him that it wasn’t necessary, he would just say that everything was taken care of. “Don’t worry,” he said, “just take care.”

At that moment, a wave of emotion hit me and I felt myself getting choked up. It might have been the relief of finding a way to execute my absurd plan. Or it might have been an act of unconditional kindness from a new friend. Anyway, not wanting to appear soft, I managed to hide the emotion and simply thanked Evan nonchalantly as though everything was cool. We went downstairs to the group and I said goodbye to everyone. The group was cheering and excitement was in the air. Finally relieved from the job of babysitting an ill-prepared foreigner lost in the middle of nowhere, everyone shook hands and told me to take care. I waved to everyone and walked off, again trying to be all nonchalant and cool.

With Uyghur bread and a backpack my only company, I waited for my van to the border.

When I went back upstairs, the lady at the office took my passport and entered my information into a computer. I was standing behind the screen and could see the list of people who crossed the border that day. There were five or six people on the list, and all of them were from Xinjiang with Chinese nationality. My name and ‘AUSTRALIA’ written in English seemed so out of place on the screen. When all the formalities were done, the lady told me to sit outside and said that she would let me know when the transport arrived. I asked a couple of times how much I owed her, but she kept saying that my friend had already paid for everything. So I went out to the empty lobby and sat at one of the tables. All the tables had fancy tea sets, and the area was spotless. Against a wall hung large flags of the Central Asian countries. I passed the time eating the Uyghur bread James had given me. Not a single person walked by the entire time. Only the bright afternoon sun filled the silence. Sitting idly as the sunlight inched across the floor, I worried that the daylight would soon fade.

After around an hour, the lady came out of the office and said something, pointing to the stairs. I didn’t understand exactly what she said, but figured that the van must have arrived. I picked up my stuff and went downstairs. The customs area was located in a large hall that took up the entire building, and I was the only person going through it. It was eerie. Echoes of random sounds occasionally broke the quiet of the open hall, dimly lit and shielded from the bright daylight outside. A customs officer behind a desk glanced at my passport and my face a couple of times and waved me through.

When I marched out of the exit on the other side, there was just an empty parking lot and my van was nowhere to be found. I began to wonder whether I had missed it. It wasn’t possible to go back to the office because that was on the other side of customs. When I walked back into the customs building, the officer noticed me from far away where she was sitting and haughtily pointed to the door with a sharp warning. She then came over and locked the door behind me. So I restlessly waited around in the empty parking lot, watching the endless parade of trucks crawling through the adjacent checkpoint.

Eventually, a small van pulled into the parking lot and another Uyghur passenger emerged from the customs building. Although the driver and the fellow passenger didn’t speak any English, a process of elimination told me that this had to be the van that was supposed to take me. My companions weren’t too interested in me and just smoked some cigarettes together while talking in the local language. After all the ups and downs I’d gone through that day to secure a transport, I half-expected the van standing right before my eyes to suddenly vanish like a mirage–because apparently, that was how my day was going. So when the driver opened the door, I jumped on the van eagerly and planted myself firmly in the backseat. By 5:20PM, the van left Kou An and I was finally on my way to Irkeshtam. I was running much later than I’d imagined, so I could only hope that the border crossing would still be open by the time I arrived. We drove through a number of checkpoints where I had to exit the vehicle and pass through buildings full of police officers. The fellow Uyghur passenger cleared these fairly quickly, but the officers took more time with me, carefully examining my passport and snapping photos of me.

The breathtaking mountain range kindled something in me, and I started believing in myself to reach Dublin on time.

The van climbed the picturesque mountain range on a lonely highway only traversed by an intermittent yet neverending stream of heavy-duty trucks. The Uyghur passenger fell asleep, and the driver was playing some songs in the local language. No one really said much, and the silence was only interrupted by an automatic beeping whenever the driver crossed the center line to overtake slow-moving trucks. The mountains were breathtaking in the literal sense of the word. Looking at them filled me with awe and left me so moved that I held my breath. As the barren mountains surrounded me, I began to grasp the fact that I had really crossed 3,700km (2,300mi) across China and now was unmistakably on my way to the Irkeshtam crossing. I had less than three weeks left to cover the remaining 7,000km (4,300mi) to Dublin. But at that moment, nothing felt impossible, and no obstacles seemed insurmountable. I started believing that, whatever happens, I would get to Dublin on time.

The scenery outside gradually changed as we gained altitude and the sun slowly started setting. We were now driving through patches of snow, and a road sign showed that the current altitude was 2,873m (9,425ft). The temperature had dropped considerably, and I began to wonder whether my worn-out down jacket would be enough to keep me warm. A horseman casually rode along the snow patches on the empty roadside. The horse was draped in a rag to keep away the cold. The sky ahead turned gray as clouds gathered. A massive line of sleeping trucks appeared ahead in our lane, and we spent a good five minutes overtaking it. The whole time, I kept my fingers crossed that no truck would come from the other direction because there was simply no space to turn around or yield.

After overtaking the sea of parked trucks, the van arrived at what appeared to be the Chinese side of the border. 7:25PM. When I hopped off the van, the harsh and cold mountain wind pounded me from all directions. There was almost nothing at the border except for some shops and a derelict building with a restroom. There were some stray trucks parked here and there, and snow-covered mountain tops were within reach. The Uyghur passenger and the driver disappeared before I could ask them for directions. I didn’t know where to go, but instinctively knew that there was no time to waste because the sun was setting and the border could be closing for the night. I walked over to the biggest building that looked like the border crossing and asked the guard at a post where to go. The guard radioed someone, and another guard came out of the building and escorted me inside.

The gushing wind and the rapidly dropping temperature at the border up in the mountain were punishing.

The building actually didn’t have any passport control for departing China. Instead, there was a customs area where one or two Kyrgyz nationals were entering China. Some Kyrgyz officers were also present and chatting in their local languages. I was taken into a small and empty waiting room with rows of steel benches. A few minutes later, a border official came out and politely interrogated me, asking where I was going and where I had been in China. He flipped through my passport and disappeared for a while. He came back and asked some more questions, such as whether I had any Chinese relatives or parents. He again disappeared while I nervously sat on the hard bench. It was cold and the daylight was vanishing outside, so I hoped I wouldn’t have to wait too long.

I sat for around fifteen minutes, then the guard came back and asked whether I was going to the US, pointing at the US visa in my passport. I confirmed that the US was my final destination. He studied the US visa with great interest and disappeared again for a while. When he came back finally, he handed the passport back to me and told me to head to passport control, which was in another building. When I stepped out of that waiting room, it was darker and colder outside with no one around. I wasn’t even sure where passport control was, so I started walking around randomly. All I could see were empty roads, and some trucks straggling toward the truck checkpoint. It was mildly amusing that, after all the troubles of getting here, I managed to get lost at the border. But I couldn’t bring myself to laugh because the night was slowly but surely encroaching.

I nervously walked around the semi-paved road that led to empty buildings when an annoyed man started shouting in a foreign language from far away in the other direction. He waved angrily, motioning for me to come to his side. He pointed his finger at his wrist and kept making exaggerated sweeping gestures with his arms. I figured he must have been the driver for the other van that Evan was talking about. From the way that he was pointing at his wrist, it dawned on me that maybe the border might be closing soon. There was no time to think. I ran and ran, with my backpack jumping up and down, and the bag of large Uyghur bread dangling uncontrollably in my hand.

I was in such a hurry that all I could see was the door to the passport control building. So I ended up running past the guard post near the building, prompting a sharp yell from the guard who was supposed to check my documents first. Realizing my mistake, I ran back to the guard who was shaking his head at the slightly out-of-breath tourist. When I finally walked into the passport control building, I found myself in yet another waiting room. The room was a lot less polished than the one I was in before. The rows of wooden benches were breaking down from years of use and were marked with graffiti. An official was sitting in the front, and two Uyghur gentlemen were waiting patiently on the benches. One of them was my fellow passenger from the van. He recognized me and smiled warmly. The other Uyghur gentleman and I struck up a conversation in basic Mandarin, and he seemed surprised to learn that I was traveling from Australia. The two travelers and the border official kept exclaiming that I was from “Aodaliya” (Australia) as if they’d spotted a leprechaun. It was possible that they didn’t get a whole lot of Australian tourists around here.

After waiting around for a while, I was called up to the passport control area. I said goodbye to the fellow Uyghur travelers who were still waiting for their turn. When I walked into the adjacent room, two guards were awaiting me at the window. They studied my passport diligently, front to back many times, scrutinizing all stamps and visas dating back years. They were also particularly interested in the US visa and spent a lot of time talking about it. After making a couple of calls, one of them disappeared somewhere and I was told to wait. In the meantime, the other guard asked me the usual questions about where I was headed, and where I had been in China. My answers didn’t seem to convince him too much, and he gave me a suspicious look. When the other guard came back, they talked for some time and my passport was finally stamped for exit.

By 8:30PM, I was on another van heading to the Kyrgyzstan border. We rode along a bumpy gravel road that stretched between the Chinese and Kyrgyz sides. Deep growls of occasional truck engines blended with the sharp howl of the wind that filled the dusty path. The driver was a friendly Uyghur man from Kashgar who said he had family on both sides of the border. We briefly made small talk, but then he started demanding an additional payment. Knowing that Evan had already paid for everything, I told the driver that I didn’t owe any extra money. The driver turned kind of sour at my response, and said that he wouldn’t drive any further if I didn’t give him 20 yuan ($3). When I asked how much further we had to go, he wouldn’t answer and kept asking for payment. It wasn’t much money, but I figured I’d rather walk or hitchhike. It sounded more interesting that way. Trucks were still passing us occasionally on the road, and I still had the last remaining minutes of daylight on my side. I hopped out of the van onto a dark and dusty road under a large overhead bridge, and the driver took off back to China.

Cyrillic writings in a stone monument, and a guard speaking Russian… I was really in Central Asia.

As soon as my feet hit the ground, I realized that the temperature was way colder than I remembered on the Chinese side and that the sky was getting dark much faster than I had expected. Worse still, most trucks were heading into China and there were virtually no trucks going in my direction. I wondered whether I had screwed up by getting off that van. But a monument on a hill caught my eye, and it sort of looked interesting from afar. The van had already left and there was no use dwelling on that. So I thought I’d check out that interesting monument and maybe figure something out afterwards. I climbed the steep hill covered with gravel and small bushes, probably looking all suspicious, while giant trucks passed occasionally and made the ground tremble all around. The stone monument said Kyrgyz Republic in Cyrillic script and it seemed to be written in Kyrgyz. I climbed down the hill and walked in the direction of Kyrgyzstan, not really even knowing which country I was currently in. Near the monument, there was a guard post with a Kyrgyz soldier, and two trucks parked on the roadside while the drivers were talking to the soldier. I probably should have grabbed every chance I had and hitched a ride with those drivers, but I saw a sunset behind the Kyrgyz mountains. And I had to stop, no matter how cold or dark. I just stood there speechless and watched the sunset.

As I mindlessly gazed at the color of the sunset painting the mountains, a Kyrgyz soldier was looking at me from his guard post. I went over to say hello and ask how far the Kyrgyz border was from where we were. It was time to put the Russian I’d been practicing with my patient colleagues to the test. To my surprise, the soldier understood me, and replied that the border was closed and I wasn’t allowed to walk there. He kept using the word “Nel’zya” (“Not allowed”). According to him, the border would be closed by the time I arrived because it was already too late now. He suggested that I come back the following morning because the border would reopen at seven o’clock. Hearing this, I realized I really had screwed up. I had already exited China, and the Chinese border was far behind me. Even if I could walk back there, would it even be open? And I wasn’t sure what Chinese border guards would make of a foreigner walking around the border in the dark. The border rules printed on the wall of the waiting room specifically said that travelers were prohibited from walking and were to take designated transport at all times. But amusingly, that wasn’t the foremost worry in my mind. I actually had a massive stomachache, probably from eating the Uyghur bread with my unwashed hands. “Gde tualet?” I asked (“Where is the toilet?”), and the soldier pointed to a dilapidated shack on the other side of the road.

When I was relieved of my bodily emergency, I began thinking clearly again and tried to explain my situation to the soldier. I told him that I was a traveler from Australia, and that I wasn’t sure if I could go back to China because I had already come from there. I didn’t know how much of what I said actually made sense, but the soldier seemed intrigued to learn that I was from Australia and glanced at the passport that I was carefully holding out for him. Suddenly he said something, and I caught the word “Mozhno” (“Allowed”). The change in his answer both confused and excited me. “Peshkom vozmozhno, da?” I kept asking the soldier in an enthusiastic voice (“I can walk there, right?”). The soldier smiled and said, “Da” (“Yes”). I was curious why he originally said that I wasn’t allowed, but I didn’t really have the mental bandwidth to form the question in Russian. And it didn’t really matter because I was desperate to keep moving and time was certainly not on my side. I just shrugged it off, thinking maybe there was a specific rule for Chinese citizens. The soldier was pretty polite and friendly to the ill-clad tourist awkwardly holding a giant bag of Uyghur bread at his side. He even helped me take a photo with what remained of the sunset behind me. “Udachi vam,” (“Good luck to you”) he said as I set off down the long stretch of road toward Kyrgyzstan.

As the sun set between China and Kyrgyzstan, the last truck left, and I was left stranded in that no man’s land.

Soon after I started walking toward Kyrgyzstan, the twilight vanished and darkness rapidly fell on the mountains. I didn’t think much of it and kept walking, but within minutes the last trace of the sunlight evaporated as though it had never been there. The sky wasn’t completely black yet, but the road ahead was barely visible. What concerned me more than the darkness was the cold. The temperature was dropping fast, and the piercing wind was hitting me head-on, growing stronger by the minute and robbing me of whatever warmth I had left. Up to this point, I’d carried a kind of naive optimism that things would somehow work out. But it finally hit me that I needed to get serious if I wanted to make it to the other side.

I dropped my backpack on the dirt, took out my only other hoodie, and put it on as an extra layer. My extremities were ice cold and I couldn’t hold on to the bag of Uyghur bread anymore. I thought about throwing it away at first, but I figured I needed some food to prepare for the worst case. I folded the Uyghur bread and jammed it into the already full backpack, breaking it into tiny pieces in the process. Then, I started walking. Against the darkening sky, I could barely make out a military guard post on top of the hills. I could only hope that I wouldn’t get into any trouble and that there were no soldiers eyeing me from that post. I went into full survival mode and adrenaline was pumping.

Somehow I was convinced that, despite all the obstacles in front of me, I had to keep walking. I don’t know why, but at that moment it felt as though the sole purpose of my existence was to take the next step headlong into that darkness. Nothing else mattered. “Haeboja” (“Let’s try”), I kept murmuring to myself in my native tongue of Korean, and slowly battled my way against the wind and the darkness, one step at a time.

What convinced me to take those foolish steps wasn’t just the obsession with following my imaginary roads. Something that night made me see that not only was it possible to reach Dublin on time, but also whether I did or not was entirely under my own control. That reminder came from nothing more than the meager steps beneath me. Simply put, by taking the next step, I was choosing to go to Dublin. If I stopped or turned back, I’d be choosing not to. The path to my destination wasn’t altogether dictated by happenstance–it was being formed by my choices. In that strange recursion of being convinced by the steps I took to take one more step forward, I continued into the darkness, mindlessly but with a full consciousness of my own choice. I was blind to anything other than the path that lay before me.

The mysterious lights in the distance simultaneously beckoned and repelled me.

In the mountains, the night ruled with an iron fist and showed no mercy. Everything around me was bearing the full weight of the darkness, and I could no longer see the road nor anything around it. The faraway mountains that had once been crowned by the illuminating glow of the setting Xinjiang sun had long since disappeared behind the black curtains of the night. The punishing burden of darkness was only occasionally lifted by the intense high beams of stray trucks that came racing from the Kyrgyz side. As their intimidating, guttural engine noise reverberated through the numbing wind, I instinctively sought refuge on the side of the road, because those trucks probably wouldn’t be expecting a pedestrian, let alone clearly see one. But the roadside wasn’t a safe haven either, because the road was perched on an elevated plain and one misstep in the dark would lead to a steep fall into an empty field.

As the night deepened, even the trucks from the Kyrgyz side stopped coming and any opportunity to hitch a ride back to China had closed. But I could see some lights in the distance. They were faint and scattered, and it was hard to tell where they were coming from. They could have been from the Kyrgyz border, or might well have been from some desolate highway. The mysterious lights beckoned me from the distance, and that made me afraid. What if, after walking all the way there, they turned out to be nothing–just another empty patch of road in the middle of nowhere? In the darkness, my senses were failing to judge the distance. I had no idea how far those lights actually were. I was pretty sure that if I had to turn back after walking all the way to those lights, I wouldn’t have the energy to make it back to China. I had already come too far and my entire body was freezing.

Those lights in the unknown distance represented both hope and the prospect of despair. That conflict mirrored my feelings about moving to the United States and about this very trip. For the longest time, I hadn’t followed those daydreams because I wasn’t sure. I was afraid of leaving the familiar world, or failing to settle into a new life or a career. I was afraid of pursuing the absurd idea of following some imaginary roads and realizing that they didn’t exist. And I was afraid of walking toward those lights. In my mind, I was briefly transported to a world, an abstract world where duality ruled. There, I saw myself helplessly caught in the pull of opposing currents of hope and despair, certainty and ambiguity, the absurd and the rational. My limbs floundering, I was struggling to stay afloat and see a direction.

The struggle on that forlorn mountain trail under the cold night sky wasn’t merely about reaching Kyrgyzstan. It wasn’t really about reaching Dublin, either. It was about life and how I would choose to approach it. Anything worthwhile has value because there is a chance of a spectacular failure. I could stay home and cling to my usual life, or seize the new life and try to live it the best way I knew how. I could choose to ignore the imaginary roads on the map, or pointlessly follow them at the risk of falling short. Already on my way to Dublin and Seattle, I had chosen to walk toward those flickering lights long before I even came here. I just didn’t know it yet.

I must have walked for half an hour in total darkness. The lights gradually drew closer, and I could finally make out tiny vehicles and structures near them. At this promising sight, I picked up the pace and cautiously passed a large object sitting on the side of the road. I could barely make out its silhouette in the scarce moonlight, and thought it was an empty container. But as I passed along its side, I realized that it was a truck, and that lights were coming from the driver’s compartment. I couldn’t tell whether anyone was inside because the truck was so huge that I couldn’t actually see inside the windshield. I ran around the front and awkwardly knocked on the bottom of the driver’s door. A moment later, someone opened the door. I couldn’t actually see the person clearly as it was too dark, but finding another person in that place brought a profound relief. The driver spoke Mandarin, so I mustered up all my high school Mandarin and whatever I’d picked up from the past week in China, and explained to him that I wanted to go to “Jierjisisitan.” The driver said something about “Zou,” which meant walking and pointed to the road ahead. I asked desperately in broken Mandarin, “Wo zou. Zou keyi ma?” (“I walk. Walk possible?”) The driver said something that I couldn’t entirely understand, but all I heard was “Keyi” (“Possible”). I didn’t want to take chances, so I asked again, “Kai men ma?” (“Is open door?”) and the driver said something affirmative. I thanked him like a madman.

When I arrived at the Kyrgyz border, there was no sign that directed the incoming pedestrians to passport control. There was just a barbed wire fence and a few soldiers walking around on the other side. In the darkness, they didn’t seem to notice me at first. The last thing I wanted was to accidentally enter Kyrgyzstan without getting my passport stamped. So I greeted the soldiers through the fence and asked where the passport control was. One of the soldiers came up, looked at me curiously and waved me over to his side. I went around the fence and carefully handed over my passport. The soldier took a cursory look at it and walked with me in silence to an old one-story building that was sitting nearby. It was the passport control office. I said thanks to the Kyrgyz soldier and walked up to the door.

The inside of the building was nearly empty. Harsh white lights were reflecting off the green paint on the walls, but somehow everything still felt dim. The bulletin board, the signs, and the lamps all looked like they had seen a better decade. Behind a desk sat another uniformed soldier. As I began to line up under the sign that said ‘passport’ in Cyrillic, he motioned me over. “Privet,” (“Hello”) I greeted him as I handed over my passport. He didn’t respond, and instead flipped through the passport in silence. He then looked up at my face questioningly, stamped the passport, and handed it back to me without a word. I said “Spasibo,” (“Thanks”) and headed to the exit, and the soldier simply glanced at me and went back to his business. Just like that, I was in Kyrgyzstan.

Weary, cold, and hungry, I had finally crossed the Irkeshtam Pass–more than twelve hours after leaving Kashgar, fresh-faced and full of energy. But it was too soon to stop and celebrate because crossing the border was only half of the problem. As I walked out of the passport control building, all that greeted me was cold, empty ground surrounded by barbed wire fences and filled in equal parts with dirt and darkness. I had crossed the border and reached Kyrgyzstan, but I remained just as lost. I needed to figure out where to go next, and this time, there was no light in the distance to follow.